It's been a little over a month since my last post. I've been living in the moment and enjoying my honeymoon travels across Europe. My journey will continue for a couple more months, after which I'll be heading to Rome to dive into a semester of study as a guest student. I am currently studying a science degree, with a double major in psychology and philosophy.

The particular place I’ll be studying at in Rome is the Angelicum. I stumbled upon this university while looking for schools in Europe that offer undergraduate philosophy courses in English to guest students. Options were limited, and discovering the Angelicum was lucky given its unusual and unique nature. The Angelicum is officially known as The Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas – pontifical universities are run by the Vatican. While many of these institutions traditionally admitted only priests, nuns, or other members of religious orders, the Angelicum has opened its doors to lay (ie. everyday) people for the past few decades.

As I have written about previously, my Catholic upbringing often influences my approach to philosophy, particularly metaphysics, grounding it in Catholic principles. However, my time at the Australian National University, a secular institution, has introduced me to post-enlightenment philosophy, shaking up many of the foundational ideas I grew up with. Studying at the Angelicum will be interesting, as it gives me the exciting opportunity to revisit philosophical topics from a Catholic perspective again, but with the benefit of new understandings and tools I've gained from studying with a scientific approach.

To prepare myself for studying at the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, I decided to delve into the works of Aquinas, the university's namesake. I had previously read some other books in the Past Masters series and found them to be both accessible and brief, but offering a more in depth account of the life and ideas of philosophers than typical encyclopedia entries. These are really good books and I will be reviewing others from the series on this substack. If you're keen, you can snag affordable second-hand copies like I did here.

Thomas Aquinas is regarded as one of the most important philosophers in the Catholic tradition, but I genuinely think he is an interesting philosopher and historical figure regardless of his theological beliefs or interests, and religious credentials. I think to be well orientated it is necessary to consider historical works even when their relevance to today might first seem distant. There's always a nugget of wisdom to unearth or, at the very least, something to be amused by (if you want to skip to the funny stuff see the “Lecture Questions” section below).

Introducing Aquinas

In Aquinas' time, there was a rift between Church officials and academic philosophers. The pursuit of rational thought often led philosophers to conclusions that clashed with Church teachings, painting reason and faith as like oil and water. To the contrary, what motivated Aquinas’ philosophical projects, was to try to marry these two things together.

Working in the 13th century, long before the Enlightenment or the Reformation, Aquinas championed the then-radical idea of approaching religious faith with reason. He didn't just accept Church teachings – instead he applied logic to explore and try to explain them. His magnum opus, the Summa Theologica, serves as a roadmap for understanding the philosophical foundations of Catholic teaching. Rather than just believing irrationally, Aquinas is about understanding why you believe what you believe. Through his work, the reader is offered a window into a pivotal chapter in Western philosophy and insight into the workings of middle ages rationality – so, let's dive in.

In 1225 Aquinas was born into a wealthy, noble family, most probably in the family castle which stood half way between Rome and Naples. At this time, vasts swathes of Europe were part of the Holy Roman Empire, ruled by Emperor Frederick II. His reign spanned territories from Sicily in the south to northern Germany and extended westward to encompass regions like Spain and Britain. Looking to the east, he captured Jerusalem during his reign. But many of Frederick’s views and goals were at odds with the Pope, who was the only other figure of similar power at play in the Western world at the time. And as Italy was where the Vatican was most powerful, Aquinas was born into a hotspot of political and cultural conflict.

At just five years old, his wealthy father sent him to live in a Benedictine (a type of religious order) monastery and receive an education. Aquinas was one of eight children and his father envisioned a monastic life for him. The monastery was in a village on the border between the Papal States (an area directly ruled by the Pope) and the Kingdom of Naples, which was more closely ruled by the Emperor Frederick. When Aquinas was just 14, the tensions between these two powers erupted, leading to the monastery's occupation by Frederick’s soldiers.

With the monastery under military occupation, Aquinas's father relocated him to the University of Naples to continue his studies. Established by Frederick just a year before Aquinas's birth, this institution was considered less susceptible to interference due to its imperial backing. It was here that Aquinas delved deeper into philosophy. And this is also where he first came into contact with Dominican preachers. Their impact oh him was profound, and in 1244, at 19, Aquinas chose to embrace the life of a Dominican friar.

At that time, Benedictine monks had a relatively high social status, as they were sponsored by the wealthy. In contrast, Dominican friars, with their vows of poverty and commitment to staying connected with peasantry, were seen as more radical. Given Aquinas's wealthy background and his family's intent for him to join the Benedictines, his choice to become a Dominican friar was nothing short of scandalous.

Though his father had passed away, the rest of his family was so angry that the Dominican order hastily planned to move him all the way from Naples to Paris to keep him safe. But his family caught wind of this plot, kidnapped him and held him in one of their castles. Over a year they tried to convince Aquinas to give up the friar life and do something more to their liking. Their efforts were in vain. Eventually, they released him, and Aquinas continued on to Paris, where he both studied and taught at the university there.

Aquinas and Aristotle

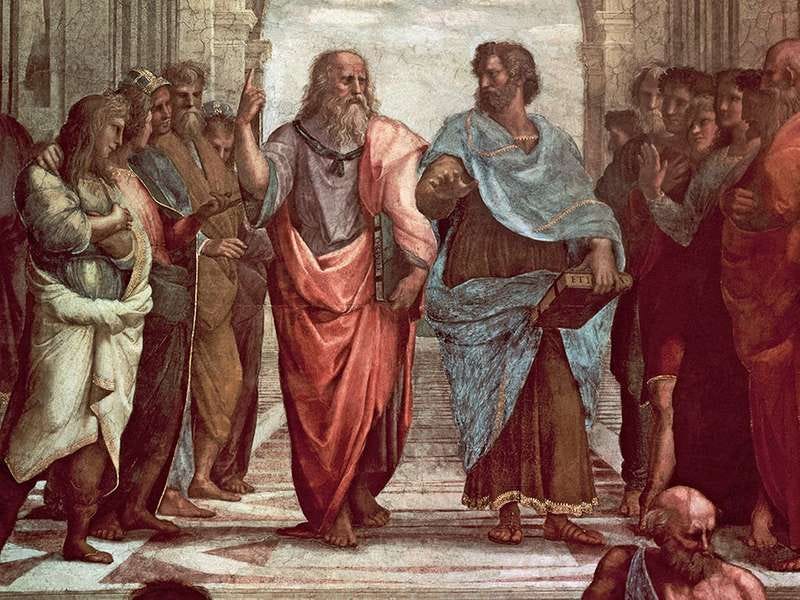

When we think of classical philosophers today, the names Plato and Aristotle spring to mind almost simultaneously. But before Aquinas’ time, only Plato’s work had been widely available. By pure chance, while Aquinas was working in Paris, a genius Dutch translator named William of Moerbeke was working on new, groundbreaking latin translations of Aristotle’s work – most of his work had been basically lost due to language barriers for almost a thousand years. When these translations came across Aquinas’ desk in Paris, he instantly recognised the brilliance and importance of them. Eager to share a wider variety of this philosophers work, he set out to popularise Aristotle's insights amongst the academic community in Paris and beyond immediately.

But why the rush to popularise more works of Aristotle, what exactly was Aquinas so excited about? To answer this, we need to first understand why Plato was already so popular. During the neoplatonic philosophy movement in the 4th century, the philosopher Augustine attempted to marry Plato’s work with Christian teachings. For undergoing this project, like Aquinas, he is considered one of the great philosophers in the Catholic tradition. But alas, Augustine left behind many philosophical conflicts, where the work of Plato and the teaching of the Church did not reconcile. Aquinas recognised that in Aristotle he had found another classical philosopher, whose wider body of work if elevated to a similar status as Plato, would allow the resolution of some of the conflicts left behind by Augustine.

To simplify, Aquinas was an early champion of Aristotle’s work, as he recognised it as a key to unlocking the door to marrying reason and religious faith – and though Aristotle seemed to be a classical philosopher of similar quality to Plato, there were less inconsistencies between Aristotles work and the teachings of the Church. Coming across William of Moerbeke’s translations was like winning the middle ages philosophy lottery.

This fluke of history was one of the most thought provoking parts of reading about Aquinas for me. Consider this – Aristotle passed away in 322 BC. Can you imagine the excitement of rediscovering his work nearly a millennium later and realising its profound relevance and utility? To properly demonstrate how Aristotle allowed Aquinas to marry reason and faith in practice, lets look a little bit into Aquinas’ ethics.

Aquinas’ Approach to Ethics

“The Summa Theologica is Aquinas's greatest work. Its foundations and its structure are Aristotelian, and many individual sections are heavily dependent on earlier Christian thinkers: but considered as a whole it is – even from a purely philosophical viewpoint – a great advance on Aristotle. It is unsurpassed by any other Christian writer, and it retains a great deal of its interest and validity for those who live in a secular, post-Christian age.”

This is how Kenny describes the quality of the Summa Theologica in the Past Masters book I read. I have paraphrased and simplified from a selection of pages from the book which describe how the Summa Theologica is informed by Aristotle and some of its key insights over the rest of this section. We begin with a high level summary of Aristotle’s ethics.

In Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle paints a picture of the ideal life – one centred on happiness. For him, happiness is activity of the soul aligned with virtue. As there are two parts of the soul, intellectual and emotional, correspondingly there are two kinds of virtue, intellectual and moral. Virtue, regardless of kind, is a mindset expressed in actions voluntarily and deliberately chosen as part of a plan of life.

Moral virtue is about striking a balance between excessive and deficient emotion and exaggerated or inadequate action – a concept Aristotle terms “the golden mean”, where each virtue stands in the middle flanked by opposing vices. For example, courage lies between cowardice and recklessness, while temperance balances indulgence and insensitivity. Justice, deemed the pinnacle of moral virtues, also seeks a balance, ensuring everyone gets what they are rightfully owed. However unlike other virtues, justice doesn't have opposing vices – any deviation from it simply equates to injustice.

But what guides us to the right action or the appropriate emotional response? That's where the two intellectual virtues come in, firstly practical wisdom, which focuses on action-oriented reasoning. The second intellectual virtue, philosophical wisdom, is concerned with speculation and learning, and is best expressed through deep contemplation. This is why Aristotle believed that the highest form of happiness is found in a life dedicated to philosophical contemplation. However, he acknowledged that such a life might seem out of reach for many. A more attainable form of happiness, he suggested, lies in a life of civic engagement and public deeds, always in line with moral virtues.

When he read William of Moerbeke’s latin translation of Nicomachean Ethics, Aquinas found support for, or at least compatibility with, Christian teachings. As mentioned earlier, the Summa Theologica is Aquinas’ best-known work and has become a roadmap for understanding the philosophical foundations of Catholic ethics. Inspiration from Aristotle starts early as the very structure of the Summa is modelled on Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics.

The Summa sets out to portray the ultimate goal of human life. Echoing Aristotle, Aquinas identifies this goal as happiness, a happiness transcending mere pleasure, wealth, honour, or physical well-being. Agreeing with Aristotle, Aquinas’ happiness is rooted in activities aligned with virtue, particularly of the intellectual kind. Aquinas proposes that the intellectual activity which satisfies the Aristotelian requirements for happiness is to be found perfectly only in contemplation of the essence of God and happiness in the ordinary conditions of the present life must remain imperfect. According to Aquinas, true happiness, then, even on Aristotle's terms, awaits in the eternal bliss of Heaven.

Virtue, according to Aristotle, concerns not only action but also feelings. Taking inspiration from this, Aquinas begins his discussion of virtue with a systematic consideration of both action and emotion. He dissects concepts such as voluntariness, intention, choice, deliberation, action and desire. While Aquinas's discourse on intellectual virtue and its interplay with emotion mirrors Aristotle's views, he soon ventures into distinctly Christian territory. He delves into three theological virtues – faith, hope, and charity. Aquinas juxtaposes these Aristotelian virtues with the virtues emphasised by Christ, especially in the Sermon on the Mount. After aligning Aristotelian virtues with Christian values, Aquinas shifts his focus to draw parallels between Aristotelian vices and biblical interpretations of sin.

The second part of The Summa delves deep into Aquinas's teachings on specific moral subjects. He closely examines each virtue, exploring its essence, and then outlines the sins that stand in opposition to it – a Christian adaptation of Aristotle's golden mean principle. He starts with theological virtues: faith, countered by sins like unbelief and heresy; hope, juxtaposed with despair and presumption; and charity, set against sins such as hatred and envy. He continues to mirror Aristotles framework when examining non-theological virtues. His analysis of justice is notably comprehensive, elaborating on various facets of criminal law, addressing issues like homicide, theft, civil claims, fraud, and even the misconduct of legal professionals.

Aquinas finally shifts his focus to the topic of piety. In Aristotle's view, piety often aligns with justice and is basically giving God his due. Aquinas view in essence agrees with this, but he is more systematic than Aristotle, delving deep into a myriad of specific topics from prayer and tithing to more obscure matters like necromancy. Also discussed is the virtue of courage, which opens the door to discussions on martyrdom and generosity. Temperance, another religious virtue, encompasses debates on ethical concerns related to food, drink, and sex. Within this context, Aquinas introduces the Christian virtue of humility. The juxtaposition of this virtue with the vice of pride allows for a reflection on the original sin of Adam and Eve. Finally, just as the Nicomachean Ethics does, the Summa contrasts the active life with the contemplative one, favouring the latter. This exploration, while echoing Aristotle, is distinctly Christian, resulting in insights on the status of bishops and the nuances of religious life.

In this section, I've focused on Aquinas' work on ethics, because it most vividly illustrates the connection between Aquinas and Aristotle. If this section piqued your interest and you dive deeper into Aquinas, you'll discover that much of his philosophical approach is rooted in building upon Aristotle's work. For those curious about where to venture next, Aquinas' philosophy of mind is a fascinating and relatively accessible starting point.

Lecture Questions

While lecturing at the University of Paris, Aquinas often took questions from students. Thanks to preserved lecture notes referenced in the Past Masters book, we get a glimpse into these question and answer sessions. While many delved into the finer details of purely philosophical topics, there were also some strange and amusing questions thrown into the mix. Past Masters didn’t always offer Aquinas' responses, but this offered me a great opportunity to engage with his work first hand – by searching through and reading some of the Summa Theologica, I tried to piece together his likely answers.

Are there real worms in hell?

This one, the book provided Aquinas’ answer for and his answer was, “no, only the gnawing of conscience” – haha!

Should monks be vegetarian?

Aquinas believed that neither monks nor the general populace were obligated to be vegetarians, based on his metaphysical beliefs about the souls of animals. However, I'd approach this explanation with a hint of skepticism. There might be a more simple and personal reason behind Aquinas' negative view on vegetarianism for monks. In his university days, Aquinas was nicknamed "the dumb ox" due to his being chronically overweight. I suspect that maybe his stance against vegetarianism was, at least in part, motivated by his own eating habits.

Can confession (when a person talks to a priest about their sins) be done in writing by sending letters or must it be done in person?

Aquinas writes specifically about this topic in the Summa. In summary, he thought that the important factor for confession is the relationship between the confessor and the priest. Therefore, he concluded that not only can confessions be made in writing – if a person is able to write but unable to see their regular priest in person – they should make confession via writing to their regular priest, rather than seeing a priest they don’t know that well in person. So there you go – a bit tedious.

Can an angel pass from one point to another without passing through points in between?

Basically, the student wanted to know if angels can teleport. In the Summa, Aquinas proposes that angels can move both continuously and instantaneously, the mode of movement depending on the situation and whether the angel assumes a bodily form. I confess, while delving into his full rationale, I momentarily questioned his reputation as a beacon of rational thought – but of course, we must remember to read this work with it’s historical context in mind.

Wrapping up this section, is one last question I came across by skimming through the Summa for my own enjoyment. (I recommend you do the same, if you’re enjoying this section!)

Can a witches spell be an impediment to marriage?

Aquinas’ answer includes a funny commentary on the existence of demons, supposedly conjured by witches. He hints at a certain skepticism about the reality of witchcraft, suggesting it might be a figment of the “common man’s” imagination. Nevertheless, he says that if witchcraft has rendered one or both parties in a marriage impotent or otherwise unable to have sex, then the marriage can be annulled. And more generally, he reckons that all other witchcraft should not pose any problem to a marriage, given that it is the work of the devil and works of God have greater strength. So there you go, now you have Aquinas’ two cents.

A Final Word

Truth be told, Aquinas lost his mind a bit as he got older. Towards the end of his life he was known to go on strange rants, even when in the presence of the King of France or other noble members of society. At 48 years old, whilst delivering a mass, he had a mysterious experience described by some as a vision and others as a mental breakdown. After this event, he never wrote or lectured again. When he was urged to continue his philosophical work, he is said to have replied, “I cannot, because all that I have written now seems like straw.” He passed away a few months later.

Three years after his death, much of Aquinas’ work was condemned by the University of Paris and University of Oxford. These condemnations coupled with the eccentricities of his twilight years, led to a lull in interest in his work. However, this dip was short-lived. He was canonised as a saint in 1323, 49 years after his death. Reflecting on his life as a whole, one might recall a saying from Aristotle, the philosopher who influenced Aquinas the most: “No great mind has ever existed without a touch of madness.”

As I wrap up this piece, I find myself in Toulouse, the birthplace of the Dominican order to which Aquinas belonged, established in 1215. By complete fluke today, I sought shade from the sun in a Dominican church, only to discover that it was the resting place of St. Thomas Aquinas. Serendipity!

Thanks as always for reading and supporting this project of mine. Though I am traveling I have packed a few books to read and write about along the way. I’m well incentivised to read and write about them – the sooner I do so, the sooner I can leave them in a hotel or AirBNB somewhere and lighten my bag!

John.